Text by Bruce Thurlow

Images from Scarborough Historical Society, Rodney Laughton and Don Googins

Scarborough has always been a place where going to sea and fishing are a part of life. At one time ships, boats, and smaller watercraft were built in Scarborough, but the town does not share the same long shipbuilding history of many other Maine coastal and river towns. There was a brief period of time, however, when Dunstan Landing was an important port and shipyard.

Shipbuilding: Sailing Ships

Shipbuilding operations at Dunstan Landing spanned the period from just after the Revolutionary War to the mid 1800s. Prior to the war, raw materials for building ships were sent to England. The area was heavily forested, much of it with tall pines ideally suited for masts and straight boards for the ships of the King’s Royal Navy. Most of the pines measured about a yard across and one hundred feet high and grew so close to each other there was no room for limbs to sprout for the first eighty feet. After the Revolutionary War, local craftsmen began building their own ships. Shipbuilding was often a side profession for those who knew carpentry. The abundance of trees, particularly the huge pines, many sawmills, a protected port and local sea captains needing ships for fishing and trade presented a perfect opportunity for building ships.

Before roads, railroad bridges and tide gates, ocean water overflowed the marsh at high tide. Boats were able to sail up the Scarborough River and over the marsh to Dunstan Landing. It was difficult to navigate larger ships, especially those carrying long masts, through the “meanderings” of the waterway, so a straight ditch was hand-dug to connect the landing to the river. In time, the rush of flowing water finished cutting a channel wide enough and deep enough to accommodate larger ships. This channel, or canal, became known as the New River. The Dunstan shipyard was at the end of the man-made canal.

Dunstan was a busy trading port as well as shipbuilding center. Lumber and fish were bought and sold; fishing fleets sailed to the Grand Banks fishing grounds; and ships sailed to England, the West Indies and other trading ports. After the British burned and destroyed Portland’s merchant fleet in 1775, trade from that port was diverted to Dunstan Landing. Since it was three miles up the river from the coastline, Dunstan Landing was a fairly inconspicuous place and less exposed to attack by the British. By the 1790s, Portland had rebuilt its port and surpassed Dunstan as a trading center.

Names of most of the ships built at the Dunstan shipyard have been lost. It is known that local mariners Abraham Perkins and Ira Milliken had two boats built at the landing, one of them a brig named Angelina. Other ships were the Velzora; a three-masted bark named Horace that was wrecked on Kennebunk Beach in 1838; and the Watchman, which sank fifty miles offshore with a cargo of coal. Some ships were built elsewhere, but launched at Dunstan Landing. Such was the Sarah, built by Major John Waterhouse near Scottow Hill and hauled about two miles to the landing by teams of oxen. The bark Delia Chapin, also built by Major Waterhouse, was the last ship built in the shipyard. It was launched as a hull in 1847 and was to be floated to Portland for final fitting out, but the ship was beached in a gale after it left the Scarborough River. It was later refloated and completed for service.

In a newspaper account of his 80th birthday, Scarborough resident Aaron A. Merrill, a Civil War veteran, recalled the days when Scarborough was a well-known shipbuilding center. His remembered that one shipyard had been at Dunstan Landing and other yards were at Black Point on the Nonesuch River and the Libby River.(1)

By the 1840s, a railroad drawbridge across the Scarborough River narrowed clearance for larger ships; and by 1873, water between Dunstan Landing and the river was diverted under the new Pine Point Bridge, totally cutting off access to all boats. The shipyard and the seaport ceased to exist.

Boat Building: Lobster Boats and Skiffs

Later, in the years between 1930 and 1960, lobster boats and skiffs were built at Pine Point. Ward Bickford built several of these boats. Three of Bickford’s boats were built in a section of a building owned by Harold Burnham.(2) Burnham had bought the old Leavitt Brothers Clam Plant, and he and family members occupied the front part that had been a barbershop. Bickford worked in the larger section that was like a one-story barn.

Bickford built five more lobster boats between 1937 and 1945. The first was built in the Pine Point Boathouse, but the building wasn’t tall enough for the cabin and it had to be put on outdoors.(3) Bickford’s next three boats were constructed in a large, garage-like structure behind the Pillsbury Inn, which was next door to his house. He built his last powerboat in 1959 for Cecil Pinkham. This boat was built on the vacant lot next to Cecil’s house; it was larger, about 34 feet, and had a diesel engine.

These particular powerboats had frames of oak and hulls made from pine strips. About 26-feet-long, these boats were built to turn quickly, were very seaworthy, and managed rough seas very well. The engine was usually a gasoline car engine. A belt ran from the engine pulley to a hauling winch; and as long as the engine was running, the winch turned and lobster traps could be hauled aboard. Except for small skiffs (punts), no other boat building has occurred in Scarborough since 1959.

Shipwrecks

Scarborough’s coastline has three extensive beaches: Higgins, Scarborough and Pine Point. There are ledges, however, around Prouts Neck, Bluff and Stratton Islands (now part of Saco) and the Graveyard (a stretch of rock ledges between Scarborough Higgins Beaches). The ledges and beaches are about seven miles toward the coastline from the bouys marking the shipping lanes. Here are the stories of some of the shipwrecks that have occurred off Scarborough’s coast.

Washington B. Thomas

The Washington B. Thomas was a five-masted schooner of a type called a fore-and-after. A fore-and-after schooner was extremely economical, because it could be handled with a smaller crew and could contain more cargo. This vessel had a brief life, for it was wrecked in June 1903 only sixty days after its launch at Watts Shipyard in Thomaston. According to Peter Dow Bachelder in his book Ships and Maritime Disasters of the Maine Coast, the ship was the largest wooden sailing ship ever wrecked off the Maine coast.

The Thomas was en route from Norfolk to Portland with a cargo of coal. Encountering dense fog off Wood Island, Captain Lermond anchored off the eastern end of Stratton Island but dragged anchor onto a ledge during a gale. A volunteer life-saving crew from Cape Elizabeth hauled a heavy surfboat more than nine miles over muddy roads to the eastern side of Prouts Neck. Three men rowed out to the Thomas and were able to get a line onto the ship and safely rescue the crew. There was one fatality earlier when the ship was struck by a large wave and Captain Lermond’s wife was struck on the head by a beam that had become dislodged. Mrs. Lermond was washed overboard and her body floated to Camp Ellis. For years, lobster fishermen knew that area of Stratton Island as the old wreck. This name was added to others around the island such as clam cove, ringbolt, and barn run.

Sagamore

Traveling in a snowstorm from Portland to New York on 14 January 1934, the Eastern Steamship Company’s freighter Sagamore punctured its hull when it struck Corwin Rock off the eastern end of Prouts Neck. In the spitting snow rescuers rowed out to assist the crew from the listing ship and all were saved. However, efforts to refloat the freighter were unsuccessful and the ship was abandoned. Part of the ship’s cargo had been bolts of heavy, double-faced woolen cloth, which were salvaged by area residents. Some Scarborough Historical Society members remember wearing coats and snowsuits their mothers made from the salvaged wool, which was tan or gray on one side and checked on the other. Masts from the wreck were visible from the cliff walk around the Neck until the 1960s.

Howard H. Middleton

On 10 August 1897, despite near-zero visibility, the coastal schooner Howard H. Middleton was under full sail as it approached Portland. The trip from Philadelphia had been slow because of contrary winds, and the captain was anxious to reach port. The captain planned to anchor behind the breakwater at the northeast side of Richmond Island at Cape Elizabeth until morning and then continue on to Portland. During the approach to the anchorage, the Middleton strayed slightly west, then north, of the intended course. Unnoticed by the crew, the ship was sailing toward high bluffs overlooking the eastern side of the mouth of the Spurwink River.

The Middleton struck a ledge off Higgins Beach and sustained a large hole in the bow below the waterline. The ship went ashore and the crew was able to debark. Although attempts were made to save the ship, all were futile and the owners abandoned the cargo, leaving it to the insurance underwriters. A Portland salvage company removed as much cargo and salvageable parts as possible, but local residents scavenged much of the Middleton’s cargo of coal. Over the years, stormy seas and wave action have continued pounding on the ship’s remains and today some of those remains can still be seen at Higgins Beach.

Fannie and Edith

On 4 December 1900 New England was hit by an extremely severe storm. Destruction to shipping was widespread, especially along the Massachusetts shore. The two-masted schooner Fannie and Edith was headed to Bangor from Boston when the schooner parted cables, leaving the ship completely at the mercy of the wind and the waves. Water had breached the breakwater at Richmond Island and the Fannie and Edith drifted westward toward Prouts Neck. Caught by a mighty wave, the ship landed high on the rocks. The crew was saved, but within a few days the 100-ton schooner was pounded to pieces on the rocks.

Cappy

Harold Seal, the author’s grandfather, was in his powerboat, the Cappy, hauling lobster traps near Higgins Beach when a southwesterly breeze started to blow. It was not a strong wind or even a rough sea. Some men of Pine Point, including Harold, would haul their traps by starting at Prouts Neck and finishing at Higgins Beach. This type of breeze usually occurred daily, but the lobster fishermen were almost always home before the wind became strong. On this day, 21 July 1951, the Cappy’s engine stopped and would not start. Harold went up on the bow and threw his newly purchased anchor overboard. The fluke of the anchor broke and the Cappy began to blow ashore. It came across the ledges and washed upon a small beach in the Graveyard area, the rocks and ledges between Scarborough and Higgins Beaches.

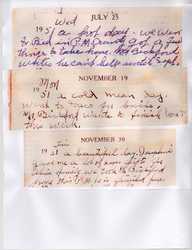

As the Cappy began to take on water, Harold swam ashore and the boat washed onto a small beach in front of what is now Piper Shores. At that time, many holes in the hull could be seen. The Cappy appeared to Harold to be a total loss. In her diary, Queenie Seal (Harold's wife; the author’s grandmother) noted, “it looks like we’re financially ruined.”(4) Barrels were tied to both sides of the boat in an attempt to haul it out. The Coast Guard could not get lines on the boat the first day, but they were successful at high tide the next day. The Cappy was brought to Pine Point and ultimately dragged to Harold’s home. Ward Bickford, who had built the boat, examined it to see what could be done to restore it. Work began and by the next spring Harold was back fishing from the Cappy. In a later diary entry, Queenie commented on the Cappy being repaired.

Footnotes

1.Maine Sunday Telegram,

2.Interview with Leonard Douglass by the author, 1 January 2010.

3.Interview with Donald Googins by the author, 24 November 2009.

4.Queenie Seal’s diary, 1951.